Like many others, I had to stay home through the COVID-19 crisis, so I decided to build a Raspberry PI cluster to explore running applications on it with Docker Swarm. In this post, I share some of the lessons I learned running the new Raspberry Pi 4 in a cluster with Docker Swarm.

Why

I’m a developer, and I’ve been interested in starting a Raspberry PI project for a while. I’m also interested in cluster computing, but never had a good reason to create a cluster. Then I read about people having great success running the new Raspberry Pi 4 in a cluster with Docker Swarm, so I thought it was an opportune time to learn more.

I kicked off this project with several goals:

- Have fun as Raspberry PIs are pretty cool hardware.

- Shift some computing resources from a home hypervisor server running VMs to the small, power-efficient Raspberry PI cluster running containers.

- Learn more about Docker Swarm.

Raspberry Pi Hardware

These are the parts I used for my project:

- Raspberry Pi 4 4GB (I bought 5).

- Heatsinks

- USB-C charge cables.

- MicroSD cards.

- USB wall charger.

- Short network cables.

- Case.

I chose the C4Labs Cloudlet case because it allowed me to access a single Pi without having to disassemble the whole case to get to it like the stackable cases. The original design of the Cloudlet case has the fans powered by the Pi. I didn’t want to have to worry about disconnecting cables if I needed to remove a Pi, so I went with the following parts to power the fans:

The Cloudlet case has plenty of room for these extra parts.

Lastly, I needed a network switch to connect the Pi devices to, but I had a spare 8-port, so I didn’t need to buy another. The Raspberry Pi 4 comes with a wireless adapter built-in, so you could use that as well.

Creating the cluster

There are tons of blog posts out there that show you how to create a cluster of Raspberry Pi with Docker Swarm. I found How to run a Raspberry Pi cluster with Docker Swarm was clear and easy to follow. All of the details you need are in that post.

Operating the Swarm

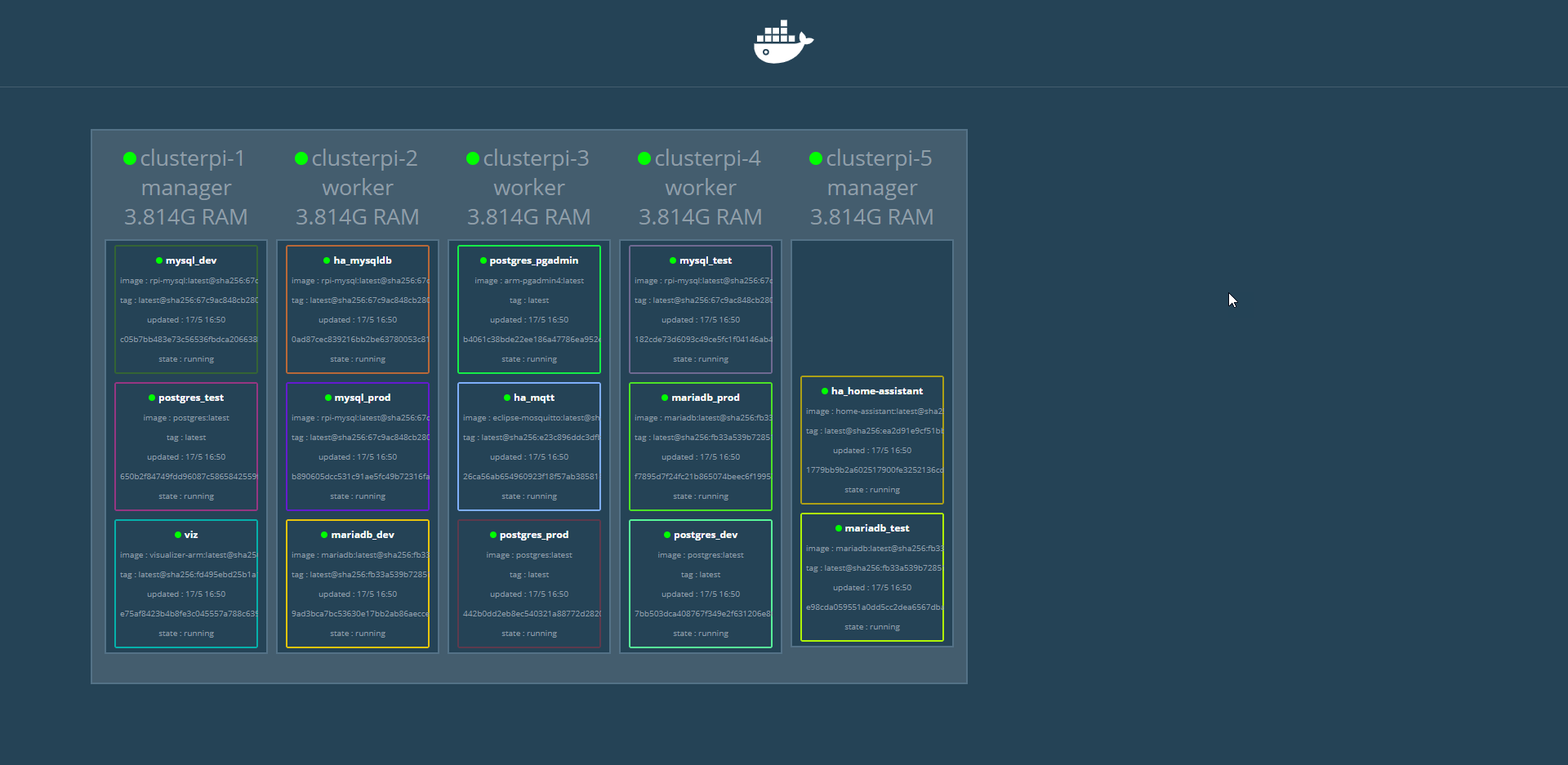

Through work, I already had some experience in working with Docker and Kubernetes (K8s), however, I’d never run a Docker Swarm. There were some new concepts to learn when running things in Docker Swarm mode versus a stand-alone Docker instance. For example, where you would normally use a docker run statement, you’d create a service within the swarm to run the container using docker service create. After messing around for a while, I had a fully operational Swarm:

Lesson 1: Not all containers run on ARM

My original intention for this project was to lessen the burden on my VM Hypervisor by running containers. When searching Docker Hub, I found that very few official images would run on the ARM architecture. I could usually find an image that someone made to run on the Raspberry Pi, but they were usually old and not the current version.

In some cases, you can use a work-around and tell Docker not to resolve the image to an architecture:

docker service create --name <some-name> --no-resolve-image <image>docker stack deploy --name <some-name> --compose-file <somefile> --resolve-image never

Lesson 2: Stacks

Stacks are the Docker Swarm way of using docker-compose. In fact, it uses a compose file as one of its arguments. Just like docker-compose, you can define multiple containers within a single file. By default, a stack deployment will create a network for the stack so they can all talk to each other. This makes it easy to refer one container to another just by name. For example, below is a compose file for running Home Assistant on my docker swarm. This stack consists of an MQTT service container, a Home Assistant container, and a MySQL database server container. For reasons I’ll go into later, I configured Home Assistant to use a MySQL back-end for the Recorder:

version: "3.3"

services:

mqtt:

image: eclipse-mosquitto

networks:

- hass

ports:

- 1883:1883

volumes:

- /mnt/clusterpi/mqtt/db:/db

- /etc/localtime:/etc/localtime:ro

home-assistant:

image: homeassistant/home-assistant

networks:

- hass

ports:

- 8123:8123

volumes:

- /mnt/clusterpi/home-assistant:/config

- /etc/localtime:/etc/localtime:ro

mysqldb:

image: hypriot/rpi-mysql

networks:

- hass

ports:

- 3350:3306

environment:

MYSQL_ROOT_PASSWORD: "MySuperSecretPassword"

MYSQL_DATABASE: "homeassistant"

MYSQL_USER: "hassio"

MYSQL_PASSWORD: "AnotherSuperSecretPassword"

volumes:

- /mnt/clusterpi/mysql:/var/lib/mysql

networks:

hass:In the configuration.yaml file of Home Assistant, you can see where I created the connection to the mysqldb container:

# Configure a default setup of Home Assistant (frontend, api, etc)

default_config:

# Uncomment this if you are using SSL/TLS, running in Docker container, etc.

# http:

# base_url: example.duckdns.org:8123

# Text to speech

tts:

- platform: google_translate

group: !include groups.yaml

automation: !include automations.yaml

script: !include scripts.yaml

scene: !include scenes.yaml

recorder:

db_url: mysql://root:MySuperSecretPassword@mysqldb/homeassistant?charset=utf8Lesson 3: Swarm members act as one

When working with a docker swarm, all of the members of the swarm act as one. Looking at the graphic above, we can see that all of the containers are distributed among the members of the swarm.

When connecting to a container via an exposed port, it’s not necessary to reference the node that is currently hosting the container. We can see that clusterpi-1 hosts the container named viz (which is the web page of the graphic, visualizer). The viz container port is mapped to the host port 80, so I can access the visualizer container web page via http://clusterpi-1. It can also be accessed via http://clusterpi-4, even though clusterpi-4 is not the current host of the container. This also means that any port that has been mapped cannot be used by another container. The mysql_dev container is the only thing that can be mapped to 3306, all of the other MySQL containers (unless they’re replicas of mysql_dev) have to use a different port.

Lesson 4: Persistent storage woes

One of the first lessons you learn with containers is that the data does not persist when the container is destroyed. In order to prevent this, you need to configure the container to map what it would usually store internally to an external volume. Creating volumes on a docker host is fairly easy. You specify a local folder to a contain folder mapping with the -v switch: -v /my/local/folder:/var/lib/data. However, this presents a problem in a docker swarm as there is no guarantee the same host will run the same container each time it is run (okay, technically, you can with constraints, but that defeats the purpose of a swarm). To solve this, we need something that can be accessed by all the members of a swarm, like a network location.

Network storage options

There are two ways this can be accomplished; Network File System (NFS) or Common Internet File System (CIFS).

NFS is usually used by Linux/Unix systems, and CIFS is what is usually used with Windows systems, though Windows does have an NFS implementation. In my home environment, I have a Windows server that I use for a file server, so I chose to use CIFS.

Configuring CIFS

This article does a really good job of explaining how to use CIFS with Linux, including how to mount a Windows share. I connected my Pi devices to my file server using CIFS with an entry in /etc/fstab, though I did have one side-effect. When I rebooted the cluster, they all came up with access to the file share, but all of my containers ended up on the Manager node. Removing the entry from /etc/fstab on one of my workers confirmed that it was indeed causing the problem.

Wait for network connectivity

The issue of all containers ending up on the Manager node vexed me for a little while. Eventually, I resolved it by adding another option to the CIFS line in /etc/fstab; _netdev. The _netdev switch delays mounting until networking has been enabled. After this was added to all Pi devices, the manager was once again able to distribute the containers.

Bypass permissions checking

Some containers alter the file system and file system permissions when starting, such as Postgres. When executing entirely within the container or a local file system mount, this is usually not a problem. However, when using a Windows share via CIFS, this usually crashed the container, stating the operation wasn’t supported. To bypass this, I found the noperm option for CIFS, which skips the permissions check and just moves forward. This allowed me to get passed that issue with Postgres, but I was never able to get a Windows CIFS share to work with the Postgres container (but that doesn’t mean it’s not possible).

CIFS and SqlLite are not friends

Having successfully configured a CIFS share for my HomeAssistant container, I found that it was having a problem with the SqlLite database that it uses by default, it kept reporting the database was locked. After encountering the same issue with the pgAdmin (Postgres management) container, I did a little Googling and found many posts describing the same behavior, with almost all of them recommending something other than SqlLite. This was the reason I included a MySql container for the Recorder service in my HomeAssistant stack deployment.

Conclusion

This was a fun a really fun project for me, and I learned a lot about Docker Swarm. Creating a Raspberry Pi cluster is great for learning concepts like Docker Swarm and Kubernetes.