Understanding the Kubernetes basics

Kubernetes basics

If you've never used Kubernetes before, it can be a daunting system to dive into. At its core, Kubernetes is an API. It acts as a way to define how you'd like your software to run. These definitions are called "manifests", and you'll generally interact with them as YAML files. The software you run in Kubernetes is generally called a "workload." Broadly speaking, there are 2 groups of components that take your manifest and attempt to make the real world reflect it:

- The control plane components

- The Node components

The control plane components are a suite of software that keeps track of all the objects and their states (both desired and actual). The Node components are the parts that run on individual machines (virtual or otherwise) to execute your workload. These machines are called Nodes, and they have a certain amount of resources available for your workloads. This includes memory, CPU time, and disk space. The control plane communicates with the Nodes using software called Kubelet, which allows the control plane to ask the Node to run a workload. This process is called "scheduling".

To allow Kubernetes to safely run your workloads, they're packaged into a special format called a Container. Container images are a snapshot of a filesystem at a point in time. These container images usually contain all the code you want to run.

When a Node begins to run the Container you've defined, the Kubelet communicates with a piece of software called a container runtime. The container runtime is responsible for isolating the code running inside the Container. This is where your workload runs.

Base Kubernetes workload concepts

We've spoken about the control plane, a Node, and a workload so far, but you need to use the Kubernetes abstractions to get Kubernetes to run something. Let's take an example of the smallest deployable concept in Kubernetes - a Pod. A Pod has one or more Containers. This is an example of a Pod definition:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: foo

spec:

containers:

- name: foo

image: hello-world

We'll break down the definition line-by-line.

This is the API version and Kind of the resource you're deploying v1 is the "core" API, which details the lowest-level building blocks of Kubernetes.

apiVersion: v1

Pod is the kind of resource we want to deploy.

kind: Pod

The metadata is information about the object, like the name, which doesn't affect the actual deployed object.

data:

name: foo

The "spec" defines the characteristics you want the resource to have - its desired state. This spec is saying that you'd like to deploy a container with the name "foo", running the image "hello-world".

pec:

containers:

- name: foo

image: hello-world

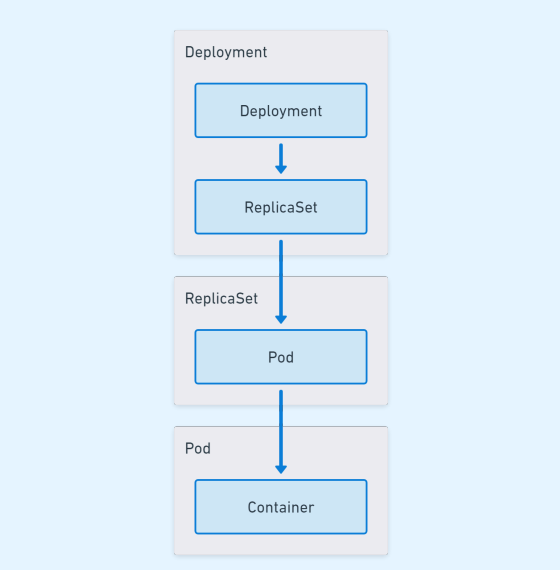

Much like building blocks, the concepts in Kubernetes build upon one another. One of the most common ways of deploying a workload is a Deployment. Deployments create a resource called a ReplicaSet, which in turn creates Pods. The following hierarchy is a simple visualization of a Deployment object in Kubernetes:

Deployment, ReplicaSet, Pod, and Container hierarchy

Deployment, ReplicaSet, Pod, and Container hierarchy

Each layer that gets created has a distinct role:

- Deployment: Responsible for controlling what happens when you want to change the deployment

- ReplicaSet: Responsible for ensuring that the replica count for a specific Pod template is always fulfilled

- Pod: Responsible for running one or more containers, providing networking and storage for the Containers inside it

- Container: The actual workload that runs

Here is a simple example of a Deployment manifest:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: foo

labels:

app: foo

spec:

replicas: 3

strategy:

type: RollingUpdate

rollingUpdate:

maxUnavailable: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

app: foo

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: foo

spec:

containers:

- name: foo

image: hello-world

Let's go through the deployment line-by-line, this time highlighting the differences:

The apiVersion is now apps/v1, and the kind is a "Deployment".

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

The metadata now adds a label as well, which you can use to filter with.

metadata:

name: foo

labels:

app: foo

spec:

The replicas field is specifying that there should be 3 replicas of the desired Pod.

replicas: 3

The "strategy" controls what happens when you update a Deployment.

- "RollingUpdate" is a deployment strategy that updates the Pods gradually, keeping some of the old online as the new gets deployed out

"maxUnavailable" specifies that when the Deployment is being updated, the old set of Pods can have a maximum of 1 Pod removed to make space for the new Pods being created

The Kubernetes documentation describes deployment strategies in detail.

strategy:

type: RollingUpdate

rollingUpdate:

maxUnavailable: 1

The selector is specifying that Pods created by this Deployment will have the label "app" set to "foo".

elector:

matchLabels:

app: foo

This is the template that the Deployment will make a Pod from.

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: foo

spec:

containers:

- name: foo

image: hello-world

Deployments aren't the only way to deploy a Pod. There are 2 other main ways to deploy a workload:

- DaemonSet: Schedules a Pod onto every Node. This is useful if you have something that should be on every Node, like a log monitoring daemon, or antivirus software. Learn more about DaemonSet.

- StatefulSet: Made for apps that need stable hostnames/identities, and are created and torn down in a specific order. This is useful if your app has roles you need to assign, but you still want to run it in Kubernetes. Learn more about StatefulSet.

Quick reference

Kubernetes building blocks

Container

- A Container is a process boundary that runs a workload in a Node.

- A Container has everything you need to run an application, including the code, any runtimes, dependencies and libraries.

- A Container runs inside a Pod, which is the smallest deployable component in Kubernetes.

Kubernetes Pod

- A Pod is the smallest deployable component in Kubernetes.

- A Pod contains all the context required for one or more Containers to run.

- A Pod controls the behavior of a Container if it exits.

- Containers in a Pod share networking and can share mounted volumes.

- Most Pod metadata is immutable, so Pods are deleted and recreated when updates are required.

Kubernetes ReplicaSet

- A ReplicaSet maintains a specified number of Pods at any time.

- A ReplicaSet contains the template that is the basis for creating additional Pods.

- ReplicaSets do not control changes such as image versions directly.

- ReplicaSets are often used as a snapshot of a Deployment at a given time.

Kubernetes Deployment

- A Deployment manages how to manage changes to Pod definitions.

- When a deployment is updated, a new ReplicaSet is created.

- The Deployment uses the defined strategy to scale down the existing ReplicaSet and scale up the new ReplicaSet.

Kubernetes StatefulSet

- StatefulSets provide guarantees that are useful for stateful applications.

- You can use StatefulSets to ensure you have 3 Pods with sequential hostnames.

- For example,

my-app-0,my-app-1,my-app-2.

- For example,

- The order in which these Pods get created and removed are the same every time.

- StatefulSets are able to use

PVandPVCtemplates to provide consistent, per-replica storage. - This allows stateful, clustered software to work efficiently in Kubernetes.

DaemonSet

- DaemonSets are intended to run a single replica on each Node.

- DaemonSets are useful for cluster services such as logging or metrics.

Storage for your Kubernetes workloads

When a Pod crashes, gets recreated, or stopped, any changes made inside the Container are completely lost. Kubernetes solves this problem by letting you define your storage requirements with volumes.

There are multiple types of volumes to account for the different requirements your workload may have. The main groups of storage types are ephemeral and persistent storage. Ephemeral storage exists only for the lifetime of the Pod, whereas persistent storage exists independently of the Pod's lifecycle.

Mounting a volume

When you configure a Pod for storage, you're mounting a volume. The 2 things you need to mount a volume are:

- A volumes definition

- This gets defined at the Pod level

- When you define a volume in the volumes section, it lets any Container in the Pod mount it

- This controls the type of volume along with any options for the volume

- A volumeMounts definition

- This is defined at the Container level

- This represents the Container requesting to mount a volume defined by the Pod

- This controls where the volume is mounted in the Container

This is an example of a Pod that is mounting a volume:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: foo

spec:

containers:

- name: foo

image: hello-world

volumeMounts:

- name: temp-volume

mountPath: /temp

volumes:

- name: temp-volume

emptyDir: {}

In this example, the volume type was defined as emptyDir, a basic ephemeral volume type. The volumeMounts settings mount the emptyDir in the /temp folder for the "foo" container. This means that when you read or write to the /temp folder in that container, you're actually writing to the temp-volume volume. Many volumes also support additional settings, for example, setting a size limit on the emptyDir:

volumes:

- name: temp-volume

emptyDir:

size: 1GiB

Types of storage

The storage types Kubernetes provide depend on the version you run. You can find a list of storage types in the Kubernetes documentation.

In the previous example, the volume was defined as emptyDir:

lumes:

- name: temp-volume

emptyDir: {}

This is an ephemeral volume type, which means that the volume only exists while the Pod does. When the Pod gets deleted, so does the volume. These volumes are useful if you want to write data that will persist through container crashes, or if you have multiple containers that need to share files. There are persistent volume types, which means that the volume continues to persist outside of the Pod's lifecycle. This can be something like a network file sharing (NFS) server, or a remote disk that gets attached, such as an Internet Small Computer Systems Interface (iSCSI).

Persistent Volumes and Persistent Volume Claims

The most common abstractions around storage in Kubernetes are Persistent Volumes (PV) and Persistent Volume Claims (PVC). A PV is like a physical USB drive in your drawer, and a PVC is someone asking you to borrow it so they can copy a file from it.

The purpose of the abstraction between the drive and the claim is to allow dynamic provisioning of PVs. A dynamically provisioned PVC is like someone asking you for a USB drive to give you a file, but since you don't have one handy, you go to the store to buy one before you give it to them.

PVs and PVCs also give you the ability to control the access mode of your volume. This lets you configure how the PV can be shared by Pods running across multiple Nodes in your cluster. This opens up options like shared caches, or storing data in an external NFS server, which can be accessed in multiple zones or regions. The access modes you can set are:

- ReadWriteOnce: Any Pod on a Node can mount the volume as read/write

- ReadOnlyMany: Any Pod on any Node can mount the volume as read only

- ReadWriteMany: Any Pod on any Node can mount the volume as read/write

- ReadWriteOncePod: Only a single Pod in the cluster can mount the volume as read/write

The configuration of PVs and PVCs is outside the scope of this document, but you can find out more by looking at the Kubernetes documentation for persistent volumes.

Storing configuration

When you deploy a workload, it's not usually in isolation. Most software needs some kind of configuration. Rather than bake-in configuration, it's much easier to decouple your app's configuration and the code. This lets you make changes without needing an application redeployment in many cases.

In Kubernetes, there are 2 main ways to store the configuration you want to expose to your workloads: ConfigMaps and secrets.

ConfigMaps

ConfigMaps are an object that stores one or more key-value pairs. The keys and values can be property-like or file-like. Generally, the configuration stored inside a ConfigMap won't be sensitive. Here's an example of a ConfigMap manifest:

apiVersion: v1

kind: ConfigMap

metadata:

name: foo-configmap

data:

# property-like keys

language: "en_us"

# file-like keys

name_list.json: |

[

"Jason",

"Emily",

"Cait"

]

Secrets

Secrets work similarly to ConfigMaps, with key-value data. The main difference is where you use the data. As the name suggests, secrets are meant for sensitive data. An example would be a connection string to a database, or in this case, the meaning of life, the universe, and everything:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

metadata:

name: foo-secret

type: Opaque

data:

meaning_of_life: NDI=

The default type of secret, and the one you'll use most often, is Opaque. An Opaque secret is simply arbitrary user data, and you can provide anything. You can find out about other types and their use in the Kubernetes documentation for secrets.

Data in a secret is stored as Base64, which lets you provide binary data like certificates easily. This is for convenience, rather than security. Best practices regarding secrets include reducing access where possible, or using external secrets where possible. Kubernetes provides some best practices for secrets in their documentation.

Consuming configuration

After you successfully decouple your configuration from your Deployment, you can configure your Pod to consume them. There are 2 main ways you can configure your Pod to consume your configuration:

- Mounting the configuration as a file

- Using environment variables

Mounting the configuration file

Mounting your configuration is generally the best way to consume your configuration. The main benefit is that the configuration file is automatically updated whenever there's a change in the source. An example of where this is useful is changing the log level of an application on the fly. One thing to note is that your application needs to support reloading the configuration file for this to be useful.

This is an example of how you can mount a ConfigMap or Secret to your Pod:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: foo

spec:

containers:

- name: foo

image: hello-world

volumeMounts:

- name: config-volume

mountPath: /etc/config

volumes:

- name: config-volume

configMap:

name: foo-configmap

In this Pod, all of the keys defined in foo-configmap show up as files in /etc/config/.

Using environment variables

If your application requires you to consume your configuration as environment variables, Kubernetes still allows you to do that. The downside to using environment variables is that they require a Pod restart to take effect, as the environment gets configured only once, at startup.

This is an example of exposing configuration or secrets to your Pod using environment variables:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Pod

metadata:

name: foo

spec:

containers:

- name: foo

image: hello-world

env:

- name: DEFAULT_NAME

value: Liam

- name: MEANING_OF_LIFE

valueFrom:

secretKeyRef:

name: foo-secret

key: meaning_of_life

- name: LANG

valueFrom:

configMapRef:

name: foo-configmap

key: language

In this Pod, the data in the language key of the foo-configmap is set to the LANG environment variable, and the data in the meaning_of_life key of the foosecret is set to the MEANING_OF_LIFE environment variable.

Networking for Kubernetes

After you have a Pod running your workload, you want to let people connect to it. By default, Kubernetes has a flat networking model, meaning every Pod gets its own IP address. Pods will, by default, be able to connect to each other. Plus, Kubernetes provides additional abstractions that let you load-balance Pods. There are a few of options when it comes to networking:

- Services

- Ingress Gateway

- API

Services

Services let you load-balance multiple Pods. Here's an example:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: hello-world

spec:

selector:

app: foo

ports:

- protocol: TCP

port: 80

targetPort: 80

This automatically load-balances between instances with the label app: foo when you connect to the service. By default, services have a Type of ClusterIP, which allows workloads running in the cluster to connect to an IP, which will automatically load balance between the currently available Pods. Other types, including LoadBalancer, indicate to Kubernetes that a plugin will try to create an external load balancer. An example would be an Elastic Load Balancer (ELB) for an EKS cluster in AWS. The types of services and their descriptions can be found in the Kubernetes documentation.

Ingress

Ingress is a way to expose application-layer configuration for inbound networking. It's most similar to a classically configured reverse proxy. Kubernetes doesn't come with an ingress provider installed by default, and there are many open-source options to consider. Kubernetes maintains a list of popular providers. Popular options include nginx, contour, and HAProxy. Many cloud providers also provide options that use platform proxy solutions, like AWS Application Load Balancers, GCE Load Balancers, and Azure Application Gateways.

Ingresses can be useful as they can capture information about requests and route them to the correct place. For example, you can terminate SSL externally, and forward to a different service based on the route:

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: Ingress

metadata:

name: hello-world

spec:

tls:

- hosts:

- hello-world.example.com

secretName: hello-world-example-com-tls

rules:

- host: hello-world.example.com

http:

paths:

- path: /foo

pathType: Prefix

backend:

service:

name: foo

port:

number: 80

- path: /bar

pathType: Prefix

backend:

service:

name: bar

port:

number: 80

This configuration will forward traffic accessed on different paths to different services, letting you balance traffic between backend services transparently.

Gateway API

The Gateway API is a new concept in Kubernetes, taking over much of the responsibility that ingress once held. The gateway API focuses on both Layer 4 (transport) and Layer 7 (application) traffic. This allows it to not only route traffic based on path, but you can choose to route based on things like the host header or the ALPN header. Although this white paper doesn't go into detail about the Gateway API, we suggest you consider using it for your ingress requirements where possible, as it will be getting new functionality while ingress remains feature frozen. You can find more details on the Gateway API site.

Kubernetes namespaces

Kubernetes is designed to allow multiple applications to coexist without impacting one another. To achieve this, Kubernetes employs namespaces to help operators logically separate components in a cluster. For example, you may have a namespace for a customer or a namespace for a certain cluster component. Not all Kubernetes objects are namespaced. For example, a PV is cluster-scoped and can be claimed by a PVC in any namespace.

Namespaces are the primary way to limit user or service account access in Kubernetes. For example, you may have a developer who should have access to update their specific application, but not another developer's application. To do this, you'd assign each developer to their respective namespace, which would prevent them from accidentally changing each other's objects.

All of the objects so far have not defined a namespace. When you define an object without a namespace, it's assigned to the "default" namespace. Before you can deploy to a namespace, you have to create it:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Namespace

metadata:

name: hello-world

After the namespace has been in the cluster, you can define it in an object to deploy it there. To define a namespace, add it to the metadata field:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: hello-world

namespace: hello-world

...

By default, namespaces are not sufficient to isolate sensitive workloads. For example, the deployed Pods can still communicate with one another. Kubernetes has well-formed guidance around the controls you can put in place.