This blog post is part 3 of my safe schema updates series. Links to the other posts in this series are available below:

Critiquing existing systems:

Imagining better systems:

- Part 2: Resilient vs robust IT systems

- Part 3: Continuous Integration is misunderstood

- Part 4: Loose coupling mitigates tech problems

- Part 5: Loose coupling mitigates human problems

Building better systems:

- Part 6: Provisioning dev/test databases

- Part 7: Near-zero downtime database deployments

- Part 8: Strangling the monolith

Many people hear “Continuous Integration” (CI) and immediately think of build servers, test frameworks and automation. Jenkins, JUnit and GitHub Actions are great, but anyone who claims that the use of these tools has earned them any CI badges is missing the point.

If Continuous Integration was about continuous builds, we’d call it Continuous Build.

Of course, testing and validation are fundamental to CI. It’s important to ensure any code that has been integrated into our main branch in source control has been through all the appropriate and necessary checks.

Regular, automated builds are reasonably uncontroversial and generally accepted. It’s this bit that involves build servers and testing frameworks. But those build scripts, and the little, comforting, green ticks, are the means, not the end. They are just one small part of a much bigger idea.

Why do we run automated builds and tests?

Most people are likely to respond with answers along the lines of “to catch bugs”, or “fast feedback”. And yes, those are great. However, that’s still only part of the story. These answers still miss the fundamental point.

Continuous Integration is about integration.

It’s, literally, as simple as that. (Word choice is intentional, and accurate.)

Most people miss the answer that’s staring them in the face. CI is about reducing the amount of Work in Progress (WIP) and avoiding big merges. It’s about breaking down broad goals into smaller (but deliverable) tasks that can be developed, tested and integrated independently. Once changes are integrated, there should be no need to “cherry pick” this change or that update from source control for deployment, because the entire set of integrated changes have already been validated as a whole. Once changes are integrated, they should be releasable with minimal risk.

Those builds exist purely to validate that our regular integrations work. After all, if we only integrate code once every three months, perhaps a one week testing phase isn’t such a pain? However, if we plan to integrate multiple times a day, a one-week testing phase isn’t going to be practical. Those builds don’t just exist to catch bugs - they exist to enable the continuous integration of deployable changes to the main source control branch - multiple times a day.

The implication is that any true Continuous Integration practitioner, will also be practicing some form of trunk-based development.

There will be some who object to the idea of trunk-based development. They may want to keep the delivery of different features/work items/tickets isolated from each other for reasons along the lines of conflicting business goals, scheduling, or co-ordination etc. For example:

- “This feature needs to be shipped after that one.”

- “This release needs to be coordinated with some marketing launch/contractual deadline.”

- “We need to fast-track this hotfix.”

- “The big scary feature isn’t ready to be deployed yet.”

Well, this is why Continuous Integration is fundamentally a project management issue, and why those fancy build tools are just one implementation detail, along with many other technical and management practices.

We need to manage our development, testing, and deployment efforts in such a manner that the issues above simply disappear. And we need to do this because the benefits of true Continuous Integration, dwarf the benefits of mere Continuous Build.

Why do we need Continuous Integration?

Have you ever worked on a 12-month project, where the 11th month was reserved for “integration”? How did that work out for you? I’m guessing it didn’t go well.

Integration phases are usually painful because all of us (and especially project managers, apparently) tend to underestimate the number of bad assumptions that have been made about how all the sub-systems are supposed to integrate. These subtle complexities don’t tend to be referenced on clean architecture diagrams, no matter how talented we are with Visio or OmniGraffle.

This leads to the discovery of more issues than anticipated. That’s annoying, but it’s not the end of the world. The real issue is that these bugs are based on code that was written 6 months ago.

We are now dealing with “load-bearing-bugs”.

OH: "You can't fix that bug. That's a load-bearing bug."

— amye (@amye) February 19, 2019

Each issue is now orders of magnitude more tricky to fix, since to resolve the problem cleanly would require a complicated refactor and probably a fundamental rethink about how this bit is supposed to work with that bit. Due to dependencies, our load-bearing bug fix is likely to have unintended consequences of its own, each of which will take time to understand and fix. Unfortunately, we don’t have the time or budget to open that Pandora’s box, so we work around it, heaping smelly workarounds on top of quick hacks and duct tape.

This all goes to demonstrate that work in progress (WIP) is a liability, not an asset. It’s a sunk cost. If your team of 8 has invested six months of dev time into some complicated new feature, that’s four developer-years of investment, probably a six-figure sum, that has been gambled on your ability to integrate the code without problems.

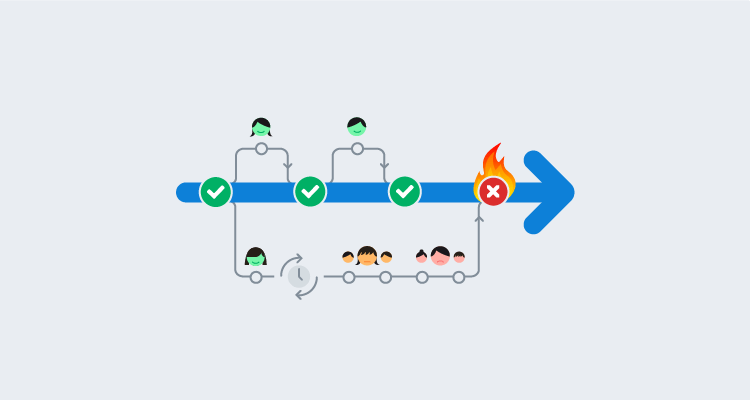

The larger the delta between a development branch and main, the more complicated the merge and the greater the chance of hitting a nasty load-bearing bug. This will take time and cost money to fix, as well as (most likely) reducing the overall quality of the code. Additionally, the more concurrent WIP, the greater the management overhead wasted managing complicated branching patterns, inconsistent development environments, brain-melting merges and hazardous, big-bang deployments. The hidden costs increase in a non-linear fashion relative to the size of the integration.

Aside from the increased cost, large integrations carry huge risk. The bigger the integration, the more likely that the integration will either fail, or the feature will be abandoned. Alternatively, it may suck up resources as either the sunk cost fallacy or human pride influences people to push the merge through, despite ludicrous risk and/or cost. The Phoenix Project is a classic example of this.

Fast-feedback is great, but automated builds won’t highlight integration issues, until concurrent development tasks are integrated. Hence, keeping integrations small and frequent is critical for the delivery of reliable IT systems.

Beyond builds, what else does Continuous Integration require?

Simply put, what would a development process that prioritized merging over diverging look like?

Of course, automated builds and tests are necessary. However, the problems CI practitioners face are so much bigger than mere builds. For example:

- How do we break down a 12-month project into zillion hour/day long tasks, each releasable individually?

- How do we balance longer term vision, with iterative learning and more agile prioritization and decision making?

- What about those tricky, big changes that take more than a day to deliver, and which can’t be shipped in an incomplete state?

- How do we manage the reliability of a submodule, when its dependencies are being updated frequently, without warning? (Without resorting to painful, manual review processes.)

- How do we manage relationships with customers/users if they still plan in terms of annual budgets, quarterly releases and infrequent software updates? What about senior management and shareholders?

- How do we manage situations where business, legal or contractual obligations necessitate infrequent, large releases?

- What does an appropriate review process look like, when we are shipping changes multiple times a day?

- How do we practice Continuous Integration at scale? How would we manage this in extremely large IT functions packed full of developers committing changes multiple times a day?

In order to solve these problems, we need to think carefully about our software architectures and the way we manage dependencies. We need ways to integrate our code and deploy changes frequently, while reserving the ability to release/reveal those updates to users on a different schedule which is optimized for commercial objectives, rather than pure engineering concerns. We need bureaucratic processes that are based on the frequent delivery of many small changes with short lead times, rather than infrequent big changes with long lead times. We need to ensure that the delta between dev and prod remains small at all times.

That’s a short paragraph with a whole bunch of big ideas. I’m not going to attempt to unpack them all in this post. Over the coming posts you can expect to see techniques to deal with many of those challenges. The point of this post is to highlight that continuous builds are only the tip of the Continuous Integration iceberg. And Continuous Integration is important.

For now, surmise to say:

- If you are running automated builds on your feature branch, but you aren’t merging your big feature with the main branch because it’s not ready yet… I’m sorry, that’s not CI.

- If you are running automated builds on your main branch, but when it comes to deploy you just cherry pick this commit or that file for deployment… I’m sorry, that’s not CI.

- If you are running automated builds, but there’s an enormous delta between your main source control branch and production… I’m sorry, that’s not CI.

- If your development environment and your production environment are wildly different from each other, perhaps with different versions of dependencies or mountains of abandoned WIP… I’m sorry, that’s not CI.

How does all this relate to safe database updates?

This mini-rant about CI might sound like a bit of a tangent, but it’s important that we understand CI properly before we go deep on loose coupling in the next two posts. Sure, smaller systems are easier to test, but there’s more to it than that, and it would be useful to go into our discussions about loose coupling and Domain-Driven Development (DDD) armed with a clear appreciation of the broader meaning and value of resilience and Continuous Integration.

Additionally, DDD is fundamentally about breaking up data models, and databases are often a shared dependency for many other systems. Loose coupling requires the decoupling of the data associated with independent services. Hence, when we start talking about the value of splitting up databases with respect to CI concerns, it’s useful to appreciate Continuous Integration in its fullest sense, rather than the shallow but widespread “continuous build” misinterpretation.

Next time

In the next two posts, we are going to switch gears and talk about database architecture - from both a technical and a human perspective. We’ll talk about loose coupling and domain-driven development, and how these principles help us to practice Continuous Integration and produce safe, resilient IT systems.

Links to the other posts in this series are available below:

Critiquing existing systems:

Imagining better systems:

- Part 2: Resilient vs robust IT systems

- Part 3: Continuous Integration is misunderstood

- Part 4: Loose coupling mitigates tech problems

- Part 5: Loose coupling mitigates human problems

Building better systems:

- Part 6: Provisioning dev/test databases

- Part 7: Near-zero downtime database deployments

- Part 8: Strangling the monolith

Watch the webinars

Our first webinar discussed how loosely coupled architectures lead to maintainability, innovation, and safety. Part two discussed how to transition a mature system from one architecture to another.

Database DevOps: Imagining better systems

Database DevOps - Imagining a better way

Database DevOps: Building better systems

Database DevOps - Building Better systems

Happy deployments!