This blog post is part 7 of my safe schema updates series. Links to the other posts in this series are available below:

Critiquing existing systems:

Imagining better systems:

- Part 2: Resilient vs robust IT systems

- Part 3: Continuous Integration is misunderstood

- Part 4: Loose coupling mitigates tech problems

- Part 5: Loose coupling mitigates human problems

Building better systems:

- Part 6: Provisioning dev/test databases

- Part 7: Near-zero downtime database deployments

- Part 8: Strangling the monolith

Small, frequent, and simple changes are safer. Big, infrequent, and complex changes are more dangerous. If you disagree, re-read this series from the beginning, starting with my post about database delivery hell.

Databases rarely exist in isolation. When making database schema changes, we usually need to consider dependencies. Databases typically serve front-end applications/services, which means schema changes often need to be coordinated with changes to other systems.

A period of downtime is probably required because we can’t risk serving mismatched versions:

- The system is taken offline

- All the changes are deployed at once/in sequence

- The system is brought back online

Throughout this process, our users are locked out.

There are a hundred ways this could end badly. The Phoenix Project featured just such a disaster. A database update took longer than anticipated and critical systems could not be restored on time.

Despite the risk, if we have database schemas, it’s unwise to avoid making schema changes. Such a rigid strategy, over time, results in horrible architectures that do not reflect evolving business requirements.

Our goal is to enable the schema to evolve safely. Therefore, we need to ensure such deployments are executed small and often.

Unfortunately, the more downtime is required for each deployment, the less frequently we’ll be able to do it. We’ll never be deploying 10 times a day if each deployment requires an hour of downtime.

More likely, engineers will need to plan well-ahead and play politics to negotiate some downtime window. Probably overnight. (Tired workers aren’t known for their reliability, attention to detail, or problem-solving skills.)

Since these opportunities don’t come often, changes will be batched up. As many changes as possible will be crammed into the shortest possible window.

This… is stupid. (See opening paragraph.)

The inescapable conclusion: It’s essential that we perform schema changes with as little downtime as possible. Only through minimizing downtime, can we increase deployment frequency, decrease deployment size/complexity, and deliver safer schema updates.

In my experience, for all the talk about source control and deployment automation, the necessity to minimize downtime is under-appreciated by those who have database schemas and wish to keep them safe.

This post is not about the automation or execution of schema updates – there are many other posts about that. This post is about patterns for minimizing downtime.

Overloaded terminology: deployments and releases

Many people use the words “release” and “deployment” interchangeably, without considering the difference between them.

If you use Octopus Deploy (or a similar product) your idea of what “release” means may be the result of common naming conventions in your tooling. In most deployment automation tools a “release” is a specific version of your source code, a bunch of configuration variables, and a set of steps that need to be run to execute a “deployment”. You might consider a “release” to be something that gets “deployed”. The release happens first, and the deployment comes later. That probably feels completely natural to you.

You are in the minority.

To most people, and specifically to anyone in marketing, a “release” is something different. “Releasing” a new version of your software, or the latest iPhone, or the new Adele album, is about making it available and telling people about it. The thing is created in advance, and released later. The latest James Bond film was produced in 2020, but the release was delayed until 2021.

When talking about zero downtime deployments, we tend to use “release” in this second way. Deployments are about making changes, but releases are about revealing those changes to our users. When I use “release” in this post, I’m not referring to the preparation of a deployment, I’m talking about making updates visible to users.

It is crucial to differentiate between deploying changes and releasing/revealing those changes to users. These two things do not need to happen at the same time. In fact, it’s the ability to separate these events that enables zero downtime releases, as well as all sorts of other exciting practices, such as testing in production and some rapid rollback patterns.

Application zero downtime patterns

This post is about database deployment, but databases don’t live in isolation. We need to start with some context.

Application deployment patterns that support zero downtime (more accurately, near-zero downtime) are generally split into two categories:

- Infrastructure-based

- Application-based

Infrastructure-based deployment patterns

Infrastructure-based techniques include blue/green deployments, canary releases, and cluster immune systems. They are typically based on clever load balancing tricks. The new code is deployed on new infrastructure, tested, and added into rotation.

By changing settings in our load balancer we can send traffic to either the new or old infra. This potentially allows us to “release” the new version gradually. First to 1% of our production traffic, then 5%, 10%, gradually throttling it as we watch the telemetry, our social media channels, and/or our support tickets to check everything is running smoothly.

If all goes well, the release will be gradually rolled out globally. If not, we can revert to the old version instantly by undoing the setting on the load balancer. We avoided any in-situ upgrades, so the old servers are still running and ready to receive the full load if required.

Application-based deployment patterns

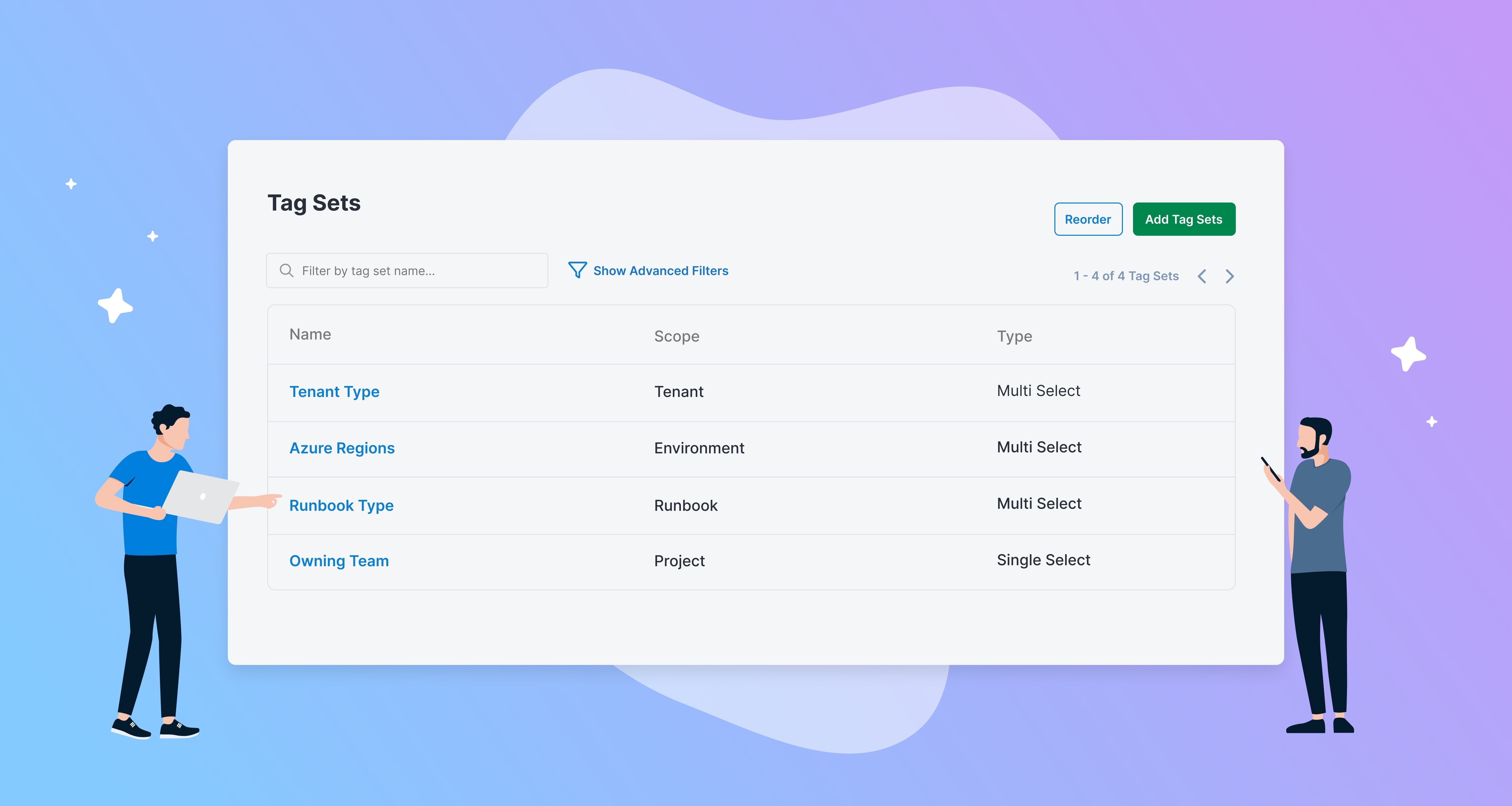

Application-based approaches tend to be based on feature-toggles/flags. The old and new version will be deployed side by side, but which version gets executed can be managed with code and some external database.

For example, perhaps we’ve got a featuretoggle database running in production. After deploying our new code, each time a method in the application is called, it queries the featuretoggle database to find out whether some feature is enabled. Depending on the response, it could run either one block of code or another. Perhaps the featuretoggle database can throttle the rollout, by instructing the application to use the new code x% of the time.

This allows new features to be released or rolled back by changing a setting in an external database. No additional deployment is necessary.

We can take this further. Perhaps, if we have a new feature, but we are concerned about performance, we could run both blocks of code, but only display the old functionality in the UI. This is called dark launching, and it allows engineers to test the performance of their code with live production workloads, with an easy way to throttle up and down or kill the new code.

You can read more about application patterns in the post Deploy != Release. This is also covered in more detail in The DevOps Handbook.

The thing that both infrastructure-based and application-based patterns have in common is that the code is deployed first, and released afterwards, in a controlled and testable manner, allowing for rapid, almost immediate, rollbacks.

What does this mean for databases? Forward and backward compatibility is essential.

Expand/contract, for forward and backward compatibility

If we wish to make a schema change in the database which will affect our dependent services, and if we wish to avoid scheduled downtime, we are likely to be following one of the application or infrastructure-based patterns discussed above. In either case, we need to evolve the database through three phases.

- Expand: Additive changes to database to support both the old and new versions of dependent applications.

- Rollout: New versions of applications deployed, tested, and released. Ideally in that order.

- Contract: Following rollout, we can safely delete the old schema objects.

This single, grand refactor is going to require multiple small schema changes. To avoid scheduling downtime, each change must have the following attributes:

- Can be executed independently of other steps or any other dependencies

- Creates minimal risk

- Has a fast roll-back option (that avoids either data loss, or significant and necessary data processing, which can cause all sorts of problems)

It’s easiest to explain with an example: Consider the splitting of a fullName column, into separate firstName and lastName columns. We can deliver this without any risky downtime windows or scary schema updates as follows:

Expand:

- The new columns are added to the database. (Nothing risky about that.)

- If using stored procedures for adding/updating/deleting data, these stored procedures can be updated to add/update/delete into both the old and new columns.

- The existing data is gradually migrated in the background. (This can be drip fed without significant performance impact and the process can be paused or stopped if there are any issues.)

Now the database supports both versions.

Rollout:

- When the data is reliably in sync in both the old and new columns, any read stored procedures can be pointed at the new columns.

- If the applications reference the columns directly, rather than going through stored procedures, rollout the new application versions using one of the infrastructure or application-based patterns described above.

Now the new stuff is released globally.

Contract:

- In theory, we can delete the old columns. However, in systems with many poorly documented dependencies, there’s always the possibility that we missed something. Better to rename the old column first. (And update any stored procedures that updated the old columns.) If anyone complains, we can immediately fix it with another rename by restoring the old version of any stored procedures.

- In either case, after some period of time, we should schedule the deletion of the old columns. No one needs to see hundreds of objects appended with

_toDelete. (Tip: try_ToDeleteOn2021-12-01instead. It somewhat focuses the mind, and we could even wrap some automated processes to backup and cull old objects.)

Refactor complete. As long as the steps are followed in this order, each step could be taken individually. None of these steps created an enormous risk. If there ever was a mistake, each step could be easily reverted.

Summary

This is a much safer way to update your schemas. Crucially, since it does not require any downtime, these changes do not need to be batched up for release.

There may be some people reading this who think it will take longer. I’m afraid those people are still thinking in terms of long lead times for small changes. Perhaps they are thinking of change approval boards or they are imagining separate JIRA tickets for each step. Perhaps they are thinking of separate week-long testing cycles for each step.

Forget all that.

If this refactor needs approval, it should be reviewed as a whole, even if it’s executed in steps. And most of the testing and deployment pipeline should be automated.

Yes: This is harder. No one said this was going to be easy. We’re optimizing for safety, and that requires rigor and effort.

Of course, with more dependencies, this is harder. Some might think it’s unfeasible. Certainly this process requires a certain level of defensive programming and testing/telemetry in any dependent systems.

In an ideal world we’d be working with loosely coupled systems (see part 4 and part 5 of my series). These are coded defensively by default and database dependencies are significantly reduced. Attributes that make all this a lot easier.

If your system is tightly-coupled, perhaps by now you are seeing the enormous benefits of loose-coupling. Perhaps you are also daunted by the perceived enormity of the challenge ahead: evolving your tangled web of dependencies into something safer.

Next time

Next time, we finish this series by exploring the Strangler pattern. A method for safely refactoring complex, tightly-coupled systems.

Links to the other posts in this series are available below:

Critiquing existing systems:

Imagining better systems:

- Part 2: Resilient vs robust IT systems

- Part 3: Continuous Integration is misunderstood

- Part 4: Loose coupling mitigates tech problems

- Part 5: Loose coupling mitigates human problems

Building better systems:

- Part 6: Provisioning dev/test databases

- Part 7: Near-zero downtime database deployments

- Part 8: Strangling the monolith

Watch the webinars

Our first webinar discussed how loosely coupled architectures lead to maintainability, innovation, and safety. Part two discussed how to transition a mature system from one architecture to another.

Database DevOps: Imagining better systems

Database DevOps - Imagining a better way

Database DevOps: Building better systems

Database DevOps - Building Better systems

Happy deployments!