With the introduction of GitHub Actions (albeit in beta), the world’s source code repository now includes the ability to host and execute your CI/CD pipelines. Now that hosting code is essentially commoditized, it was natural and inevitable that running build scripts would be commoditized next.

The interesting thing about CI is that it’s a machine driven process that will run when the inputs (like your latest commit) are available, and generates the outputs (like your artifacts and test results) without intervention. Over the years we’ve seen every major CI platform continue to distill the build pipeline down to this formula through the concept of pipelines as code, with the result being that CI user interfaces are used as little more than a read-only dashboard, and CI servers become build agent orchestrators.

So given GitHub Actions hosts the code, exposes the build pipeline as code, provides the execution environment to run those pipelines, and provides a repository to host the resulting artifacts, do you even need a CI server any more?

To answer the question of maintaining a dedicated CD server, you should read the post The differences between Continuous Integration and Continuous Deployment.

Top reasons to ditch your CI server and move to GitHub Actions

As an experiment, I decided to migrate an open source project to GitHub Actions. This allowed me to replicate a reasonably complex test and build pipeline on GitHub’s new service, and it revealed a lot of reasons to love it.

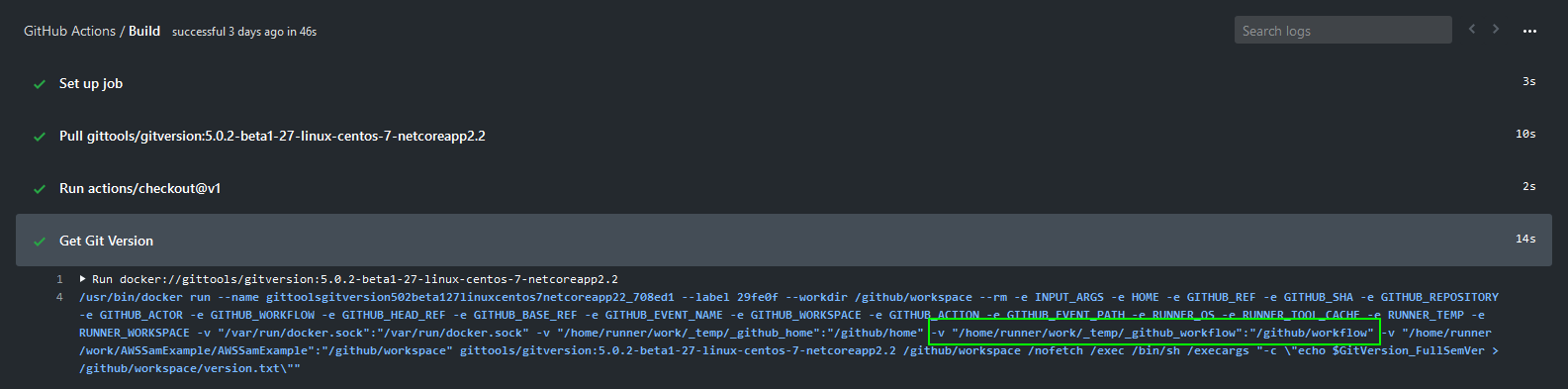

At the heart of GitHub Actions is the idea of composing your build environment from Docker containers. At a high level, your workflow is a series of jobs, and each job can either be a script run directly on the underlying virtual machine or execute a Docker container that shares the virtual machine’s file system through a volume mount.

The highlighted area shows the mounting of the virtual machine file system into a Docker container used as an Action.

Composing your build environment in this way is brilliant because every major development tool already has a supported Docker container ready to use, and you are forced to no longer maintain build agents that are works of art (which is to say, build agents that have been manually tweaked and maintained over the years). There is some overhead to getting the workflow jobs just right, but this effort pays off multiple times over in the long run. It also means incremental changes to the build process can be tested in a branch without spinning up custom build agents, which is increasingly important when you consider that even dinosaurs like Java and .NET now have major releases every six months.

Having GitHub host the execution environment now means that forks also inherit the build environments. This is a huge win for open source project maintainers, who no longer have to consume code changes in order to run complex regression tests in their own build environments, and contributors can be confident their changes will pass any required tests.

And, let’s face it, everyone is going to hop on the GitHub Actions train. Your favorite integration tools are guaranteed to have either a custom Action one or a Docker container easily used as an Action.

But GitHub Actions aren’t quite ready

There are some gaps in GitHub Actions that you need to consider before making the jump though.

First, versioning your builds is kind of a pain. GitVersion provides a workaround, but the lack of an incrementally increasing build number variable to use inside your workflows is a surprising oversight.

There is no easy way to share secrets between repositories, which means if your microservice CI/CD pipeline includes a push to a cloud provider, every repository needs to include a copy of your credentials. This will be difficult to maintain as keys are cycled.

Capturing output variables is not supported at all. If you look at how we implemented GitVersion, you’ll see that the output of the command was saved to a file because the filesystem is the easiest place to share output between actions. It would have been nice to capture that version in a variable rather than printing the content of a file and passing the result to subsequent command-line arguments.

While GitHub provides an impressive list of operating systems to run your builds on, if you have to test any flavor of Linux beyond Ubuntu or older versions of Windows and MacOS, you will still need to provide your own test environments.

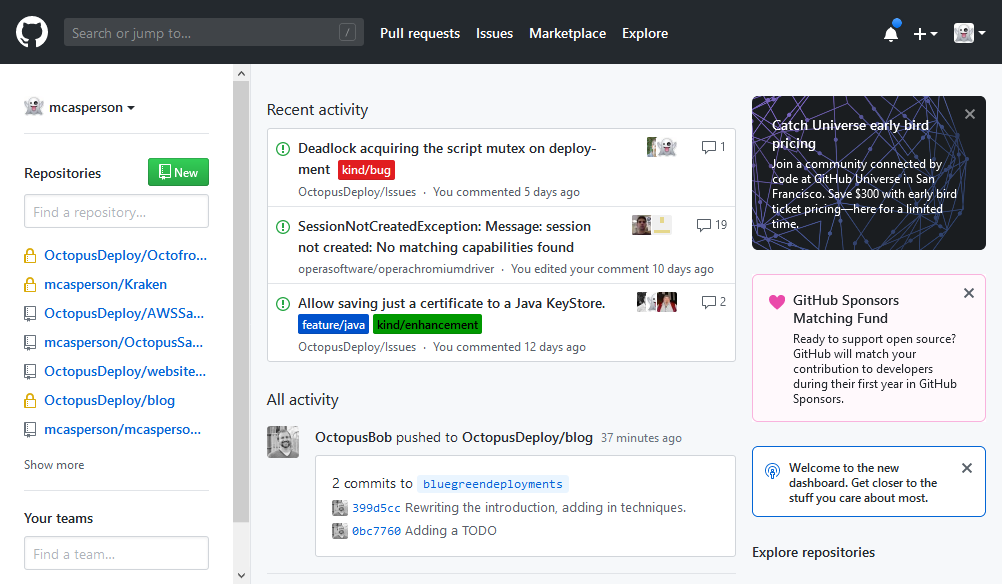

Finally, the GitHub UI is still repository centric. Knowing which repos have actions defined, let-alone trying to view the state of your builds is clunky at best. Expect to click around a lot if you have many projects built with GitHub Actions.

You won’t find the status of your builds on this homepage.

Conclusion

GitHub Actions is ideal if you maintain a small number of open source projects. Contributors can fork your code and build environments, and you no longer have to maintain any separate build infrastructure.

But once you start scaling up beyond a few projects, the GitHub UI works against you. Also, any complex builds will have to find workarounds for capturing output variables and sharing secrets.

Having said that, GitHub Actions are in beta, and a lot of these inconveniences may well be solved in the future. If GitHub can provide a build centric dashboard and smooth out a few of the rough edges in the workflows, you’d have to seriously question whether you wanted to maintain a dedicated CI server.

GitHub Actions is yet another example of the industry commoditizing low hanging fruit. Combine the fact that developers have already done the hard work of placing their build pipelines into code with cloud computing dropping the cost of infrequently executed code down to almost zero, and it’s not surprising that code repositories have provided a way to execute those pipelines. The challenge is now for providers that consume the built artifacts to continue to add value to the CI/CD process.