This document uses Producer and Consumer frequently. To avoid confusion, use these definitions:

- Producer - the user who creates and manages process templates in Platform Hub.

- Consumer - the user who uses the process templates in their deployment or runbook processes.

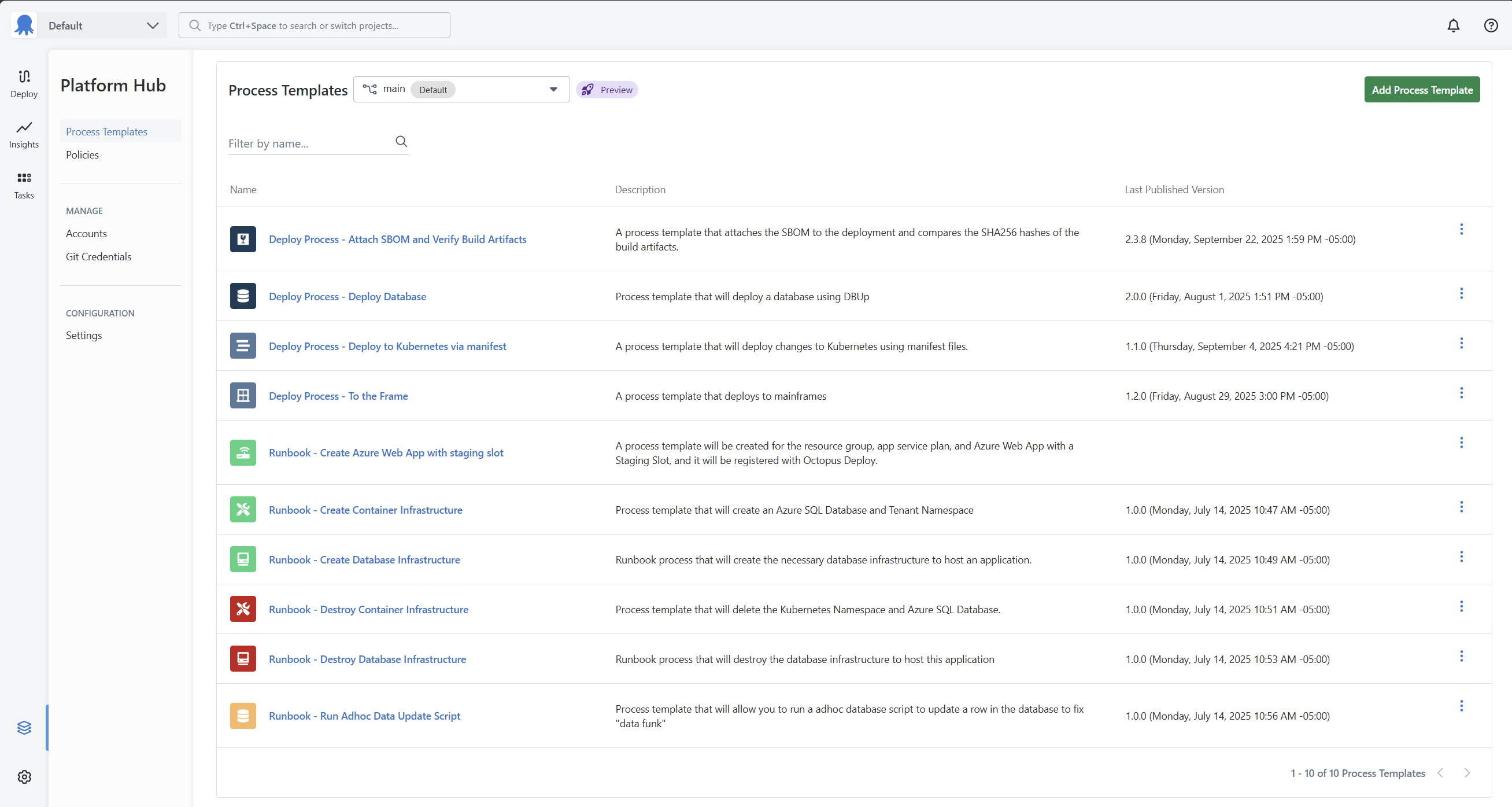

Process templates administration

Establish a naming standard

Use a [ Prefix ] - [ Template Name ] that is easy for everyone to understand the template’s purpose. The [ Template Name ] should be succinct and informative.

The [ Prefix ] should inform everyone where the template should be used. For example:

- Deploy Process - [ Template Name ] for templates designed for deployments only.

- Runbook - [ Template Name ] for templates designed for runbooks only.

- Deploy and Runbook - [ Template Name ] for templates that can be used in deployments or runbooks.

Establish what the major/minor/patch/pre-release means to your company

Process templates’ versioning provides hints:

- Major (breaking changes)

- Minor (non-breaking changes)

- Patch (bug fixes)

- Pre-Release

There will be confusion unless you define what a breaking vs. non-breaking change means to you and your company.

A starting point of a policy can be:

- Major — The change requires the consumer to test it. The template changes how it fundamentally works, and it might delete existing parameters or add new ones. A consumer updating the template requires a PR in their project.

- Minor — The change generally doesn’t require the consumer to test it extensively, but it might have added or removed a parameter, which will require a PR by the consumer because it changes the deployment process.

- Patch No parameters were added or removed, and testing isn’t required (except by the consumer who reported the bug). The consumer doesn’t require a PR as the deployment process OCL doesn’t change.

- Pre-Release - Use for changes that aren’t ready for general use.

Leverage branch protection policies on the Platform Hub Git repository

Template changes should occur in a branch and be reviewed via a PR. To test the changes, use the Pre-Release feature within the versioning functionality.

Building Templates

Opt for several smaller templates over “all-in-one” templates

Creating a single process template containing all the steps required to deploy an application can be tempting. In practice, the “all-in-one” template falls apart at scale.

Not all applications use the same components

Consider this example:

- Application #1 - Deploys a container to Kubernetes with a SQL Server Backend

- Application #2 - Deploys a container to Kubernetes that monitors a queue

No matter what, you will create two templates.

- Option #1 - Create a template for each application combination

- Kubernetes + SQL Server

- Kubernetes + Queue

- Option #2 - Create a template for each component

- Kubernetes

- SQL Server

With option #2, you’ll have templates that can be mixed and matched with other application types. For example, the SQL Server template can be used for .NET apps running on Azure Web Apps, Linux, or Windows.

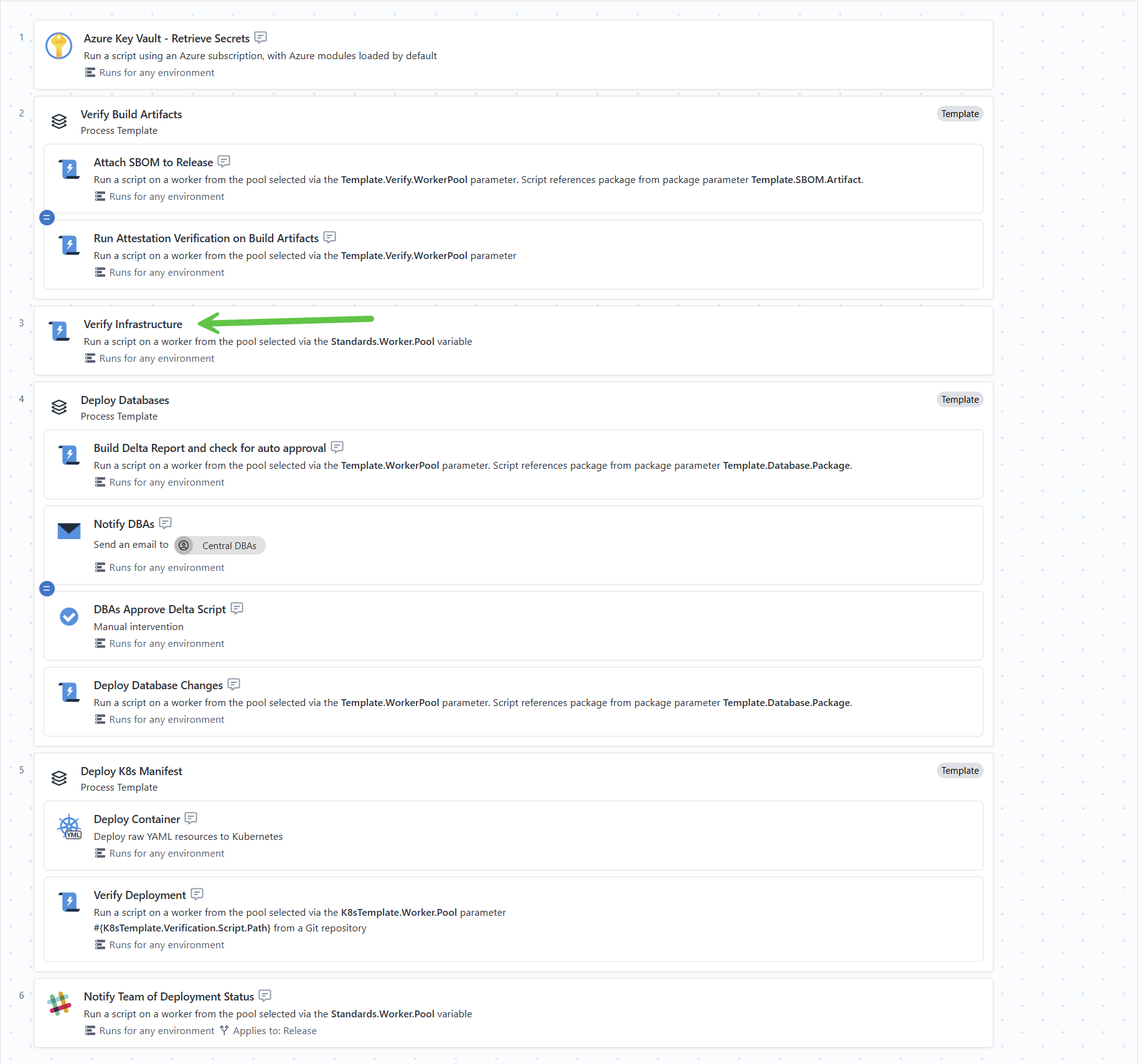

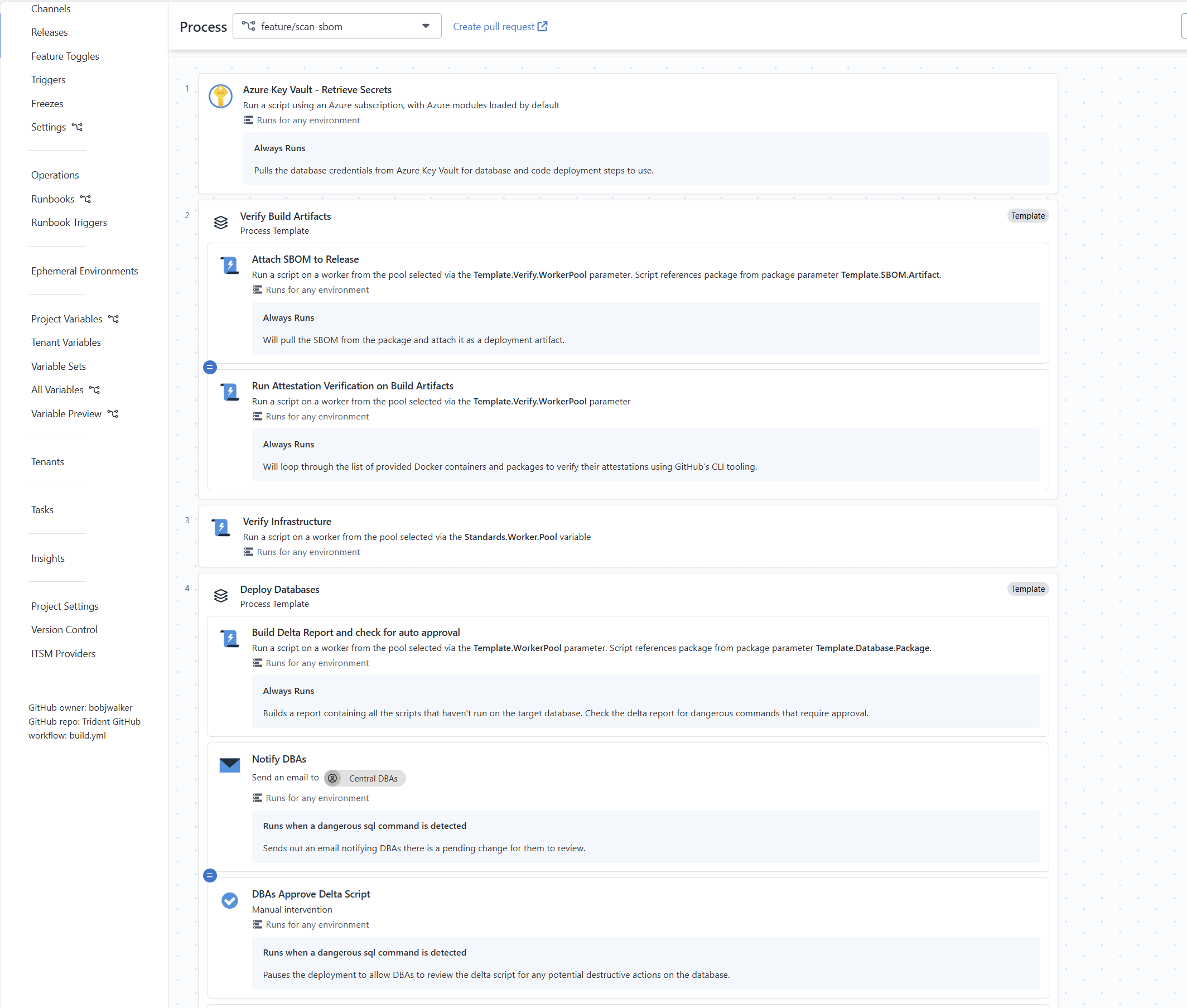

Some applications require steps before or after templates

Consider this deployment process:

It uses three process templates, but they don’t all run back to back to back. Between the first process template, Verify Build Artifacts, and the second process template, Deploy Databases, a step to verify the infrastructure runs. Not all applications need that specific step to run between those templates.

Having multiple process templates allows application teams to insert steps before or after specific actions are performed.

A template for everybody is a template for nobody

A large all-in-one template requires significant complexity to account for multiple use cases. We’ve seen all-in-one templates follow the same pattern:

- The template starts out simple.

- More use cases are encountered and additional steps are added. Steps solely focused on business logic and creating output variables become the norm.

- Conditional run conditions for multiple steps become the default. The template becomes very brittle as people need to “hold it just right” for everything to work.

- Conditional steps start to fail randomly, or steps are skipped randomly because of a configuration change.

- Consumers are forced to update the templates repeatedly to fix the ever-growing list of bugs.

- Consumers start asking for the ability to cherry-pick steps when running the template.

Eventually, the template becomes unusable, and users want a complete rewrite or ask how they can get out of using the templates.

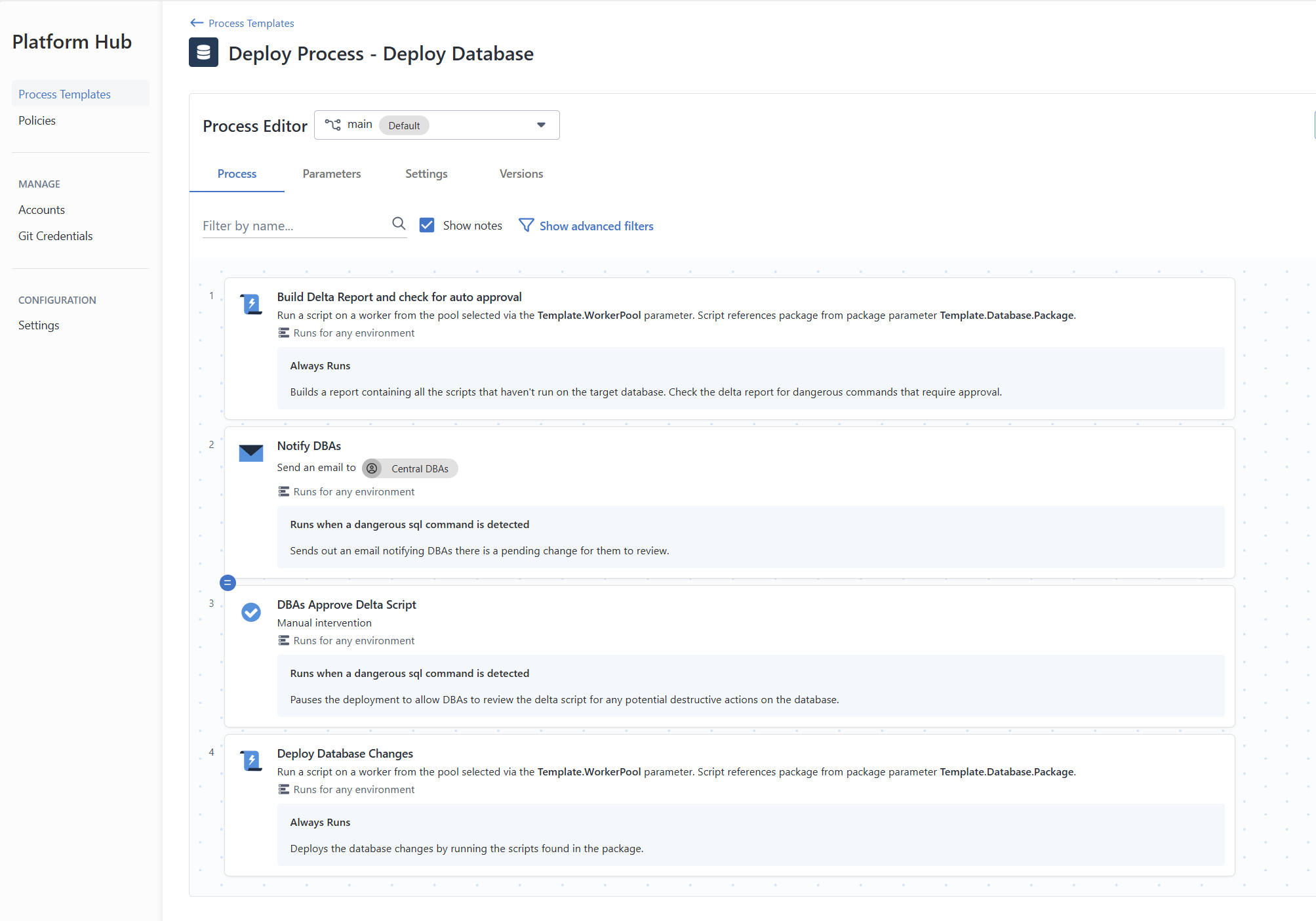

Follow the single responsibility principle

A template should have a single purpose. That doesn’t mean a single step, but a singular purpose that is easy for consumers to understand. Some examples include:

- Template to create a database on a server

- Template to destroy that database

- Template to verify build artifacts

- Template to deploy and verify an application on a Kubernetes cluster

- Template to deploy a database change

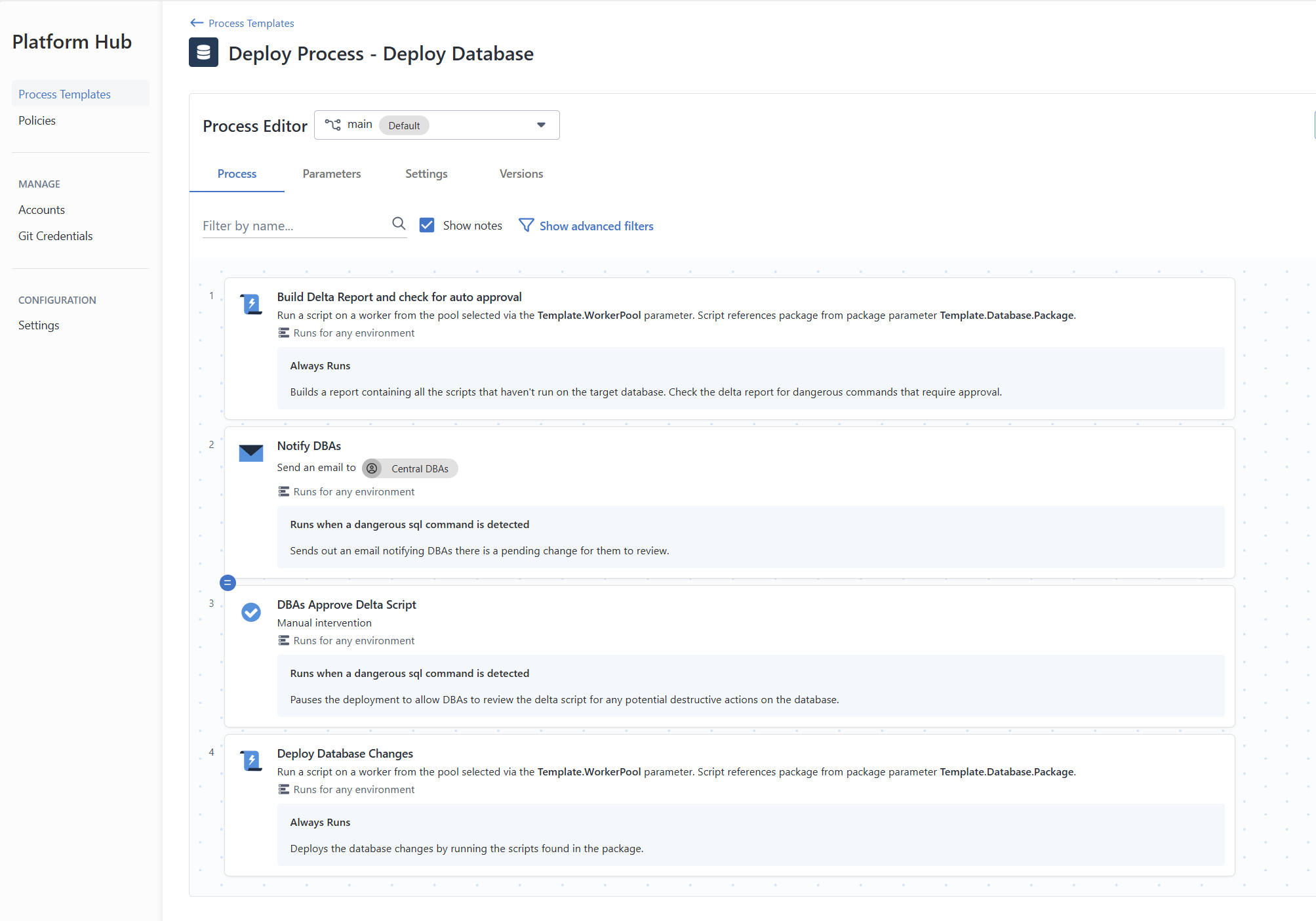

The template should include all the necessary steps to accomplish that task. Consider a template to deploy a database change. The company policy might be build a delta report and verify it before deploying. But DBAs don’t need to be bothered with every change, so only bother them when specific commands appear. For example, Drop Database. To accomplish that, the template would be:

Parameters

Parameters should be the only way for information to be sent from consumers’ deployment and runbook processes to process templates.

- Templates should not explicitly rely on output variables from other process templates. Template B shouldn’t have a hard-coded output variable from template A.

- Templates should not hardcode the names of project variables or variable set variables. They must be sent in via parameters.

- Any external references for items outside of Platform Hub - secrets, feeds, worker pools, tags - must be sent in via parameters.

Templates must be self-contained

A template should not expect other templates to be included in the deployment or runbook process.

- Use parameters for all inputs.

- The consumer, not the producer, should determine the order of the templates in the process. The consumer has context regarding the order of component deployments.

- All steps needed to accomplish the template’s task must be included.

Keep consumer decision-making to a minimum

The consumer shouldn’t need to worry about:

- The number of steps required to accomplish a task

- The steps that can be skipped based on a decision within the template (alerting a DBA if the Drop Database command is found)

- The specific logic of how a task is accomplished.

A consumer should be able to say:

I want to deploy to Kubernetes and verify the deployment using this information:

- The container URL

- The Git repository of the manifest files

- The path to manifest files in that repository

- The target tag of the cluster to deploy to

- The verification script to run

It is the producer’s job to figure out how to takes those parameters and deploy the container to Kubernetes.

Include notes for each step in the process template

Notes help the consumer understand the intent behind each step. If a deployment fails, it is easier for them to self-service why the failure occurs if they have that context. Sometimes, a step name is all that is required to understand the intent. However, assuming everyone will understand the context based on the name alone is dangerous. It is better to include notes by default.

Producer-managed script steps in templates

A process template has two options for the Run a script step.

- Consumer-managed script steps, such as running a verification step after a deployment. The producer will not know the necessary tests to run, so they will ask the consumer to provide the script for the tests.

- Producer-managed script steps, such as creating a delta report from the provided database package and looking for dangerous commands. The script is created and managed by the producer to accomplish the goal of the template.

This section refers to the latter, producer-managed script steps.

Store the script inline with the template

Since the template is already in version control, referencing another git repo for the script is redundant.

If multiple templates need to reference the same script, that indicates they are doing too much. They likely aren’t following the above best practices (single responsibility principle, self-contained, etc.).

Output variables intended for business decisions should only be used by the template

It is common for a script step to make a set of decisions and create an output variable. For example, the first step in this template looks for dangerous commands in the migration scripts and sets an output variable when those commands are found.

Those kinds of output variables should only be used by the template itself.

Output variables must be surfaced via logs when intended for outside steps to use

When a template explicitly creates output variables to be used by other steps they must be logged for the consumer to know. For example, a template that retrieves values from a key vault and sets them as output variables.

- When possible, allow the consumer to provide a list of output variables - for example, telling the key vault which secrets to retrieve.

- When that is not possible, log all the output variables created.

- If another process template will use those output variables, they should be sent in as parameters. There should never be a hard link between templates.

Log everything

Octopus supports different levels of logs:

- Write-Verbose - writes a verbose log (hidden by default)

- Write-Info - writes an info log (visible on task log screen by default)

- Write-Highlight - writes the information to the task summary screen

- Write-Error - writes an error message

Use those log levels and write messages frequently. This aids in debugging when a deployment or runbook run fails. Logs are like an umbrella - better to have it and not need it than need it and not have it.

Help us continuously improve

Please let us know if you have any feedback about this page.

Page updated on Thursday, September 11, 2025